In the long and illustrious filmography of Hsiao-Hsien Hou, Dust in the Wind is arguably his most underrated masterpiece. Coming right after a series of coming-of-age films The Boys from Fengkuei (1983), A Summer at Grandpa's (1984) and A Time to Live, A Time to Die (1985), the film failed to match its predecessors success at film festivals and was also a box office flop back home in Taiwan during its initial release. It was only later that the film gained a strong cult following among cinema fans, film critics and scholars, and it is now widely regarded as one of Hou’s definitive masterpieces. In a poll conducted during the 50th edition of the Golden Horse Awards, many filmmakers and critics picked Dust in the Wind alongside City of Sadness as their “Best Chinese film” of all time!

Hou was voted "Director of the Decade" for the 1990s in a poll of American and international critics put together by The Village Voice and Film Comment

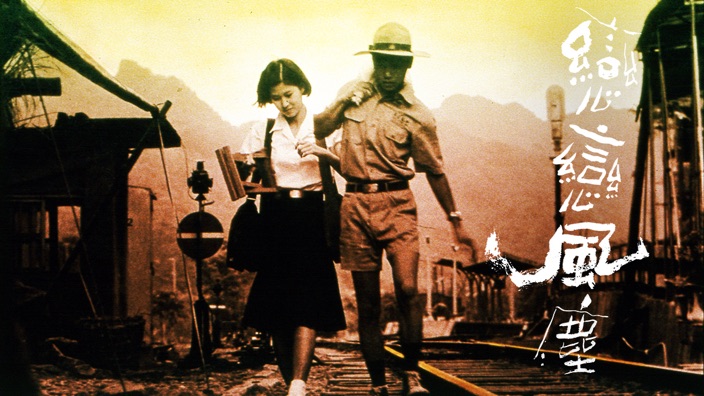

Set in the 1970’s, the narrative of Dust in the Wind follows the bittersweet romance of Huen (played by Shu-fen Hsin, one of Hou’s regular actresses in the 80s) and Wan (played by first-time actor Chien-wen Wang in his only screen credit) as they moved from their rural hometown of Jiu-fen to the urban setting of Taipei to seek better economic prospects.

Hou’s trademark long takes and static camera shots are taken to the extreme in Dust in the Wind

What made Dust in the Wind stand out as a sublime piece of art is Hou’s minimalist direction and aesthetics, an accumulation of the style that developed throughout his work in the 1980’s. Hou’s trademark long takes and static camera shots are taken to the extreme in this film, more so than in his preceding work. The average shot length (ASL) of The Sandwich Man, his first foray as a Taiwan New Cinema director, was sixteen seconds per shot. Both The Boys from Fengkuei and A Summer at Grandpa's averaged around eighteen to nineteen seconds per shot, and with A Time to Live, A Time to Die the ASL increased to around twenty-four seconds. In Dust in the Wind, however, the average shot was over half a minute. With each progressing film in his Taiwan New Cinema period, Hou pushed his shots to be longer and even more static, though that does not make it any easier to be emulated by other directors. The trick lies in the complex staging and subtlety of the actors’ movements within the frame, as well as in his shot composition. Whether it’s a low angle framing of a tight interior location (hat tilted to Ozu, who Hou has often been compared with), or a wide exterior shot of the beautiful mountain landscapes, the intricately composed cinematography is certainly a key contributing factor to the poetic realism of the entire film. Dust in the Wind also marks Hou’s second collaboration with Mark Ping-bin Lee, who would go on to become the most regular cinematographer to work with Hou, all the way from the mid-1980’s until The Assasin (2015).

Huen (Shu-fen Hsin) in Dust in the Wind

The music score, composed by Chen Ming-Zhan, comprises of only acoustic guitar and flute and also fits well with the minimalist approach of the film’s aesthetics. The music comes in intermittently to create the mood and acts as a transition between scenes. Trains and train stations have become a recurring motif in many of Hou’s films, and in Dust in the Wind, this motif played a pivotal role right from the opening shot of the film, as the camera closes in on a light that reveals a train passing through mountain tunnels, going in and out of the darkness, suggesting an ever changing transition through physical space and time. This iconic shot also acts as a metaphor for cinema, which is another recurring motif of this film. Both the leading characters, Huen and Wan, stay with a friend who works in a cinema as a painter of movie posters which are featured prominently in many scenes. Back in their home village, in contrast with the claustrophobic atmosphere of the urban cinema, the villagers organise an outdoor movie screening that fittingly pays tribute to Lee Hsing’s Beautiful Duckling (1960), a pioneering work of the “Healthy Realism” film movement of the 1960s, which can be regarded as an older distant cousin to the 1980s Taiwan New Cinema, as both movements strive to present social realist themes, albeit in different ways.

Lee Hsing’s Beautiful Duckling (1960), a pioneering work of the Healthy Realism film movement of the 1960s, which can be regarded as an older distant cousin to the 1980s Taiwan New Cinema

In terms of inspiration, Hou continued to tell nostalgic personal stories in a progression, starting from A Summer at Grandpa's (inspired by scriptwriter Chu Tien-wen’s childhood), A Time to Live (Hou’s autobiographical coming of age story) and finally Dust in the Wind, which was inspired by scriptwriter Wu Nien-jen’s own personal experiences. After Dust in the Wind, Hou appears to have reached a point where he could no longer go on relying upon his own recollections or those of his co-writers. Hou briefly made an attempt at doing a commercial movie, Daughter of the Nile (1987) starring pop idol Yang Lin, which was an artistic failure despite featuring Li Tianlu (who also appeared in Dust in the Wind) as a wise and comical grandpa character.

A City of Sadness is the first part of Hsiao-Hsien Hou’s Taiwanese History Trilogy and is now hailed by many critics as a masterpiece

Moving on to the next stage, Hou transferred his vision deeper into Taiwan’s historical past as he embarked on the Taiwanese History Trilogy that started with the hugely successful Golden Lion winner City of Sadness (1989) which actually saw Hou revisiting the picturesque location of Jiu-fen. With the critical and commercial success of City of Sadness, the former mining town of Jiu-fen has since become a tourist attraction. But it is with Dust in the Wind that Hou first fully realised his style of filmmaking and firmly established his status as a film auteur. It is highly recommended to visit his earlier personal works from the 1980’s before watching the master filmmaker experimenting with an even bigger canvas and more ambitious scope in his later films.